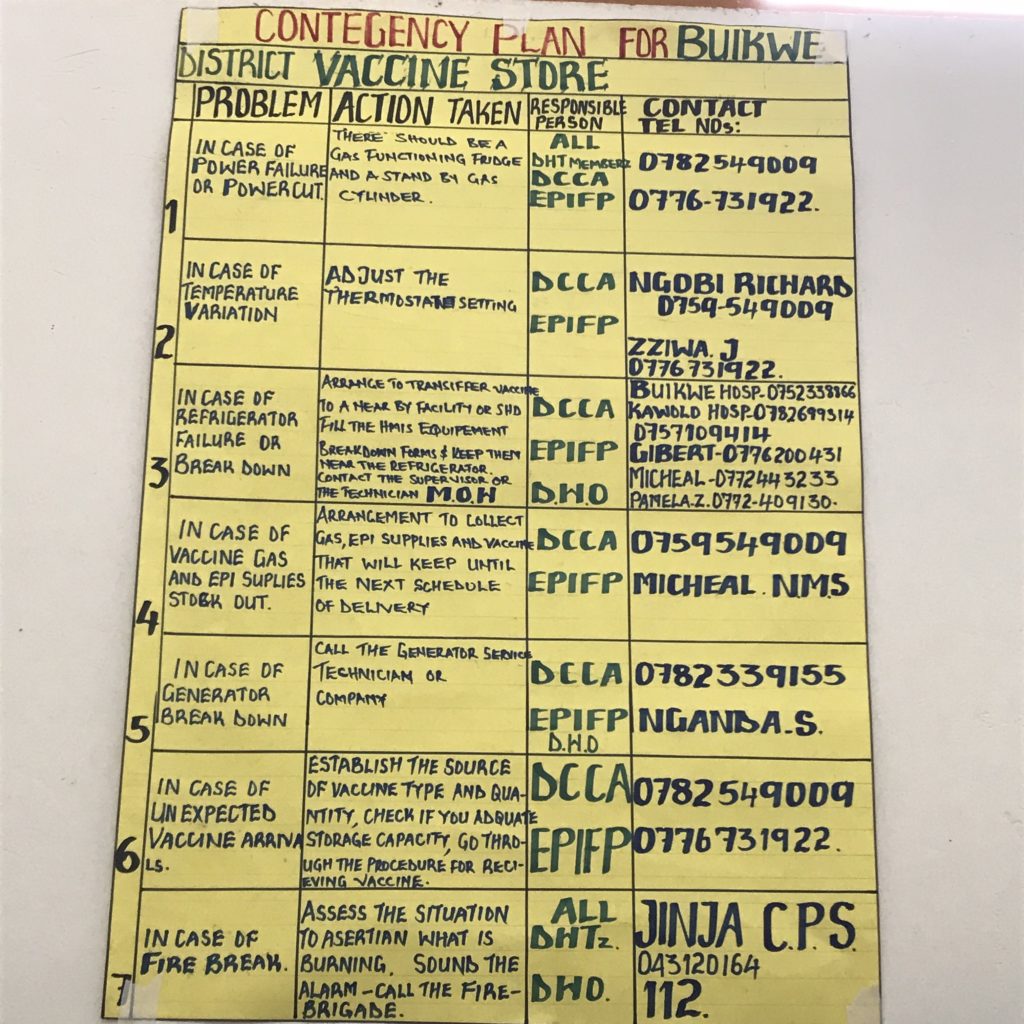

I traveled to the Buikwe district of Uganda to see first-hand the roll-out of the rotavirus vaccine in that area. I expected to leave with memories and images that would stay with me and inform my advocacy work. What I did not expect was that one of those images that would stick in my head would be of a handwritten poster taped to a wall above a vaccine refrigerator.

In neat and careful printing on yellow poster board, someone had carefully outlined the possible issues with vaccine storage and what the response should be. The poster is a clear illustration of what could go wrong in the cold chain. The cold chain is defined by the CDC as “a temperature-controlled environment used to maintain and distribute vaccines in optimal condition.” The vaccines must stay at a temperature that keeps them both safe and effective.

I was aware of the importance of the cold chain, but this poster and the refrigerators made it clear how challenging it can be to maintain it. It is precarious.

Possible challenges to the cold chain include:

- Power failure

- Refrigerator failure or breakdown

- Generator malfunction

- Fire

GAVI provides generators in some locations to lessen the impact of power outages. Power outages are far more common in developing countries than they are in the United States.

Appliance stores and repair professionals, however, are far less common. The refrigerators we saw bore a variety of stamps, indicating that the Ministry of Health, GAVI, and other partners had worked together to purchase them and deliver them to this district facility. Many efforts contributed to keeping the vaccines at the perfect temperature.

Unfortunately, however, refrigerators do not last forever. When a refrigerator breaks in a developing country, particularly in a more rural region, there are not many people who can repair it. Even if someone can fix it (we were told by a Ugandan health official that YouTube videos can be very helpful), extra parts are not always readily available. Generators, too, sometimes do not work exactly as they should.

Due to all the possible problems, every single day someone checks the temperatures and monitors the equipment at the district health office where the vaccines are stored. Weekends and holidays are no exception.

Since traveling to Uganda, I have thought often of those monitoring vaccines to make sure they are stored in optimal conditions with the cold chain perfectly maintained. They always come to mind on holidays. When I am preparing a celebratory meal and in and out of my refrigerator gathering items, I wonder who is checking the vaccine temperatures of the storage refrigerators in that facility and in other countries around the world. I feel immense gratitude for their dedication and I cross my fingers, hoping that the vaccines are the temperature they should be.

When I think of the poster, I am also struck by the fact that it lists only the potential pitfalls in that one location. Transporting the vaccines from where they are manufactured to the Buikwe district of Uganda comes with its own myriad of challenges. Similarly, securing the vaccines in coolers and getting them to clinics can also be difficult, particularly when workers travel on boda bodas (small motorcycles) over dirt roads to remote locations in less than ideal weather conditions.

Of course, there are also threats that come from unexpected sources, such as political turmoil, economic upheaval, or natural disasters.

The cold chain must be maintained to provide children around the world with safe, effective vaccines. While there are many things that can go wrong, I was so gratified to see the vaccines administered in Uganda and to know that so much had gone right. Seeing children receive lifesaving vaccines that would protect them and knowing all the efforts that went into maintaining the cold chain to make that possible warmed my heart.