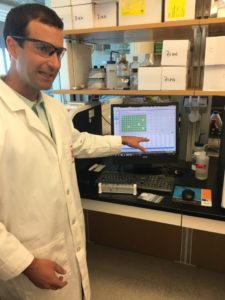

A CDC scientist discusses a diagnostic tool that tests for a range of parasitic diseases in a single test.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC is in partnership with both the WHO and UNICEF in various global health areas, particularly working to prevent polio and measles outbreaks around the world. Our group spent the day with senior officials from CDC’s Center for Global Health and toured the agency’s pioneering research labs to learn more about their incredible work protecting Americans at home and abroad by helping countries stop deadly and debilitating diseases at their source.

We learned that these global health activities – which range from efforts to eradicate polio and measles to strengthening the public health workforce and improving countries’ disease outbreak response capabilities – contribute to a broader initiative called the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA).

The GHSA provides countries with a framework to measure their ability to prevent, detect, and respond to public health threats. The CDC has committed to assisting dozens of countries to strengthen areas of GHSA. However, with funding set to expire in Fiscal Year 2019, the agency would be forced to drastically scale back their efforts by 80 percent, leaving only small-scale pilot programs in just a few countries.

Slashing funding for CDC global health efforts would not be in America’s interest. The agency is on call 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, to assist public health officials across the globe, and is often called the “Reference Lab for the World.”

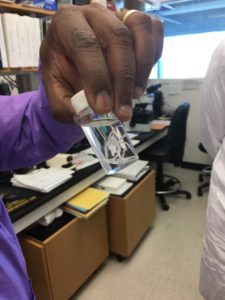

In the parasitic disease labs; one of the last remaining guinea worms in the world. This sample was sent to CDC for identification only a few days before we arrived.

The Parasitic Disease Lab, for instance, performs over 800,000 parasitic disease tests a year, from all over the world. In one case, scientists in the lab received an urgent request to identify a parasite that was discovered while a doctor was operating on a patient. CDC scientists identified the sample and responded within 40 minutes – while the physician was still operating!

Our visit emphasized that people are at the heart of CDC’s work. The agency amplifies their expertise through various fellowships and exchange programs, including the Field Epidemiology Training Programs (FETP), which develops a global workforce of “disease detectives” on the frontlines of emergency response.

Since 1982, the FETP program has trained over 10,000 graduates from more than 65 countries, and since 2005 these practitioners have performed over 3,300 disease investigations, from Ebola in West Africa to Polio in Pakistan and Nigeria. One recent FETP graduate, a physician from the Democratic Republic of Congo, was deployed to contain an outbreak of Yellow Fever less than a week after returning from the program.

These programs provide technical training but even more importantly establish a deep network of personal connections in national and local health offices around the world. During public health emergencies, these connections open lines of communication to speed faster and more efficient outbreak response. This training also provides a pathway towards sustainability: As one CDC official explained, “Our goal is to improve country capacity and expertise until they can take the reins.”

Our visit underscored the value of CDC’s global health activities and provided tangible examples to our congressional delegation of how CDC is keeping Americans safe and improving global health every day.